Leaving El Salvador at La Union, we climb aboard a small passenger ferry to cross a bay that carves the shores of El Salvador, Honduras and the border into Nicaragua at a very small port called Potosi. The small boat manages the choppy water quite well, taking none of the seasick passengers prisoner, and we arrive bobbing in the water just several feet away from the sandy shore. Local men waiting along the cement ramp venture into the water to carry our bags on their shoulders and heads as we dig into our pockets for tip money. And then we descend from the ladder hung on the side of the ferry and wade through thigh high water, walking onto Nicaraguan soil like refugees. There awaiting us is the customs and border control: a rough cut wooden table painted in Nicaraguan blue.

In line to get the forms filled and our bags opened for weapons inspection, I notice the stray dogs here are leaner, hanging onto life with skin and bones. The peoples’ expressions tighter, hungrier and their hands open to begging. Once all in our group have passed muster, we climb aboard a new van. Driving through the countryside on our way to Leon, further differences mark the country from its neighbors. Its streets are noticeably flatter and smoother. Our guide tells us the Chinese have found an opportunity in “helping” them with infrastructure and goods, but are really buying and investing in large swaths of their land and importing a lot of their own goods which does little to help the Nicaraguan workers. Despite the improved road quality, horses hitched to wooden carts clop down congested city streets, which appear to be a common source of transportation for produce or people, as are the Toyota pick up trucks that offer standing room only in their beds for men and boys on their way to work. They hold onto the frame as they sway into the turns. The heat intensifies in the cities with little greenery for shade, the diesel fumes spew in unregulated glory; construction, with jack hammers pounding, competes with boombox music blasting out from hole-in-the-wall bric-a-brac stores, all of which make navigation along narrow sidewalks tedious. Every sense, opened for observations and discoveries, becomes simultaneously bombarded.

I walk along the narrow streets which here are also paved in cement, some more recently done than others, and look for the French bakery one of us found on last evening’s walk around. I pass men of any age who look upon me to assess whether an opportunity of any kind is in the offering. It’s the look of desperation, opportunism, chance, need. From the women, I notice a softening of their eyes and expression, as if they too, like the stray dogs who follow you for a while, or the grocery bag you’re carrying, have learned how to change their facial gestures to evoke from you empathy or compassion. And then I find the bakery, after I pass a boy who should be about 12 and in school, sleeping along the sidewalk, deeply unconsciousness.

Feeling the incongruity in the realties of their lives and mine, feeling almost like a spectator in an arena of sports and games of day-to-day survival, I nevertheless hasten into the cafe and sit in the back garden, sip a cafe Viennese and the Nicaraguan version of a chocolate croissant: a sweet, plantain paste center dotted with dark chocolate and surrounded by powdered sugar sifted pastry dough.

The next day we board the van to Granada. Lighter, wider, a city with an international influence as seen by the restaurant options and English books on shelves therein. Still, the vendors at the tourist kiosks call you over on the main Calle, the restaurant hosts wave and hand you menus as you walk past to entice you in. It’s a hawkers’ paradise.

A scenic boat ride on Lake Nicaragua is on the daily agenda the next day. We spot monkeys and osprey. Small islands dot the shore; some inhabited by local fishermen for generations; some lived on only occasionally by the wealthy. Some are for sale with a present day median price of $500,000. Many are owned by coffee plantation and bank owners; a few wealthy expats who use nearly every dry square footage for foundation or wall for their large houses. Close by are the indigenous people, in shacks with thatched roofs.

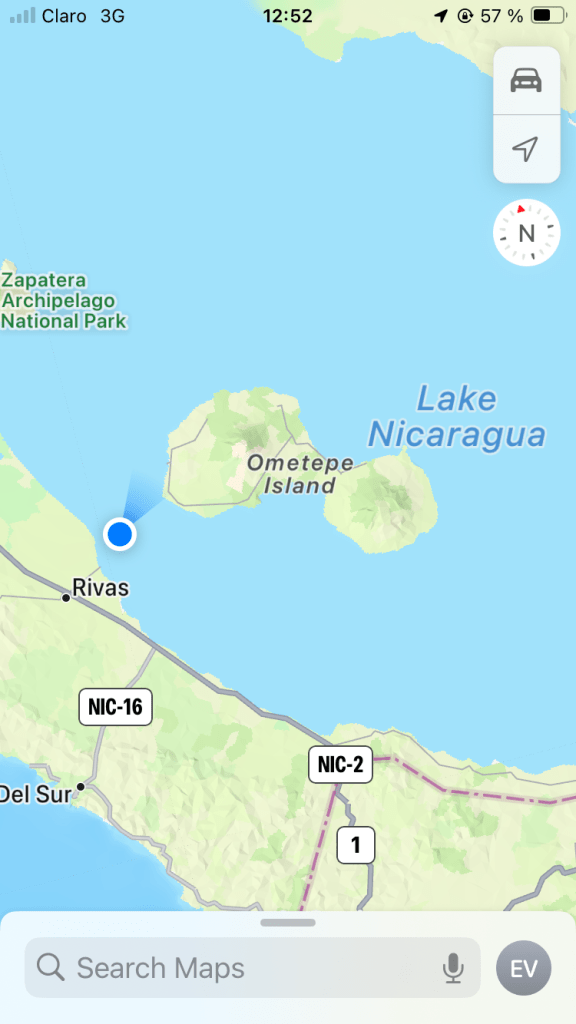

The next day we board the van again and head south past Riga and into St. Jorge, where we take a loud local passenger and goods ferry to Ometepe Island, formed by two volcanoes in Lake Nicaragua. The passage takes an hour, and I have to use earplugs to block the engine noise sputtering somewhere close by my seat. The exhaust pipe reaches upward from the boat’s bowels and then turns itself into the direction of the seats in the back, into the faces that f the late comers and unsuspecting first-time ferry going foreigners. An excruciating hour later, moving along at a very slow speed with an engine sounding like it’s about to give out, we arrive on the island.

After a welcome briefing by the island locals who are hosting us for two nights, we relax by the lake with a beer and dinner, a Nicaraguan dish of beef, rice, fried plantains and loads of vegetables.

The next day, some in the group rent scooters and motorcycles and tour the island; others take the van to a waterfall, a swim, and a petroglyphs viewing. I and two others choose to climb a volcano. Cautioned that this hike is of the “extreme” category and that only very experienced hikers need apply, I lace up my only feasible pair of shoes that have served me well on the cobblestones and simple dirt paths so far. I haven’t brought true hiking shoes, but got the ok from the guide who checked that our attire was volcano hiking sturdy.

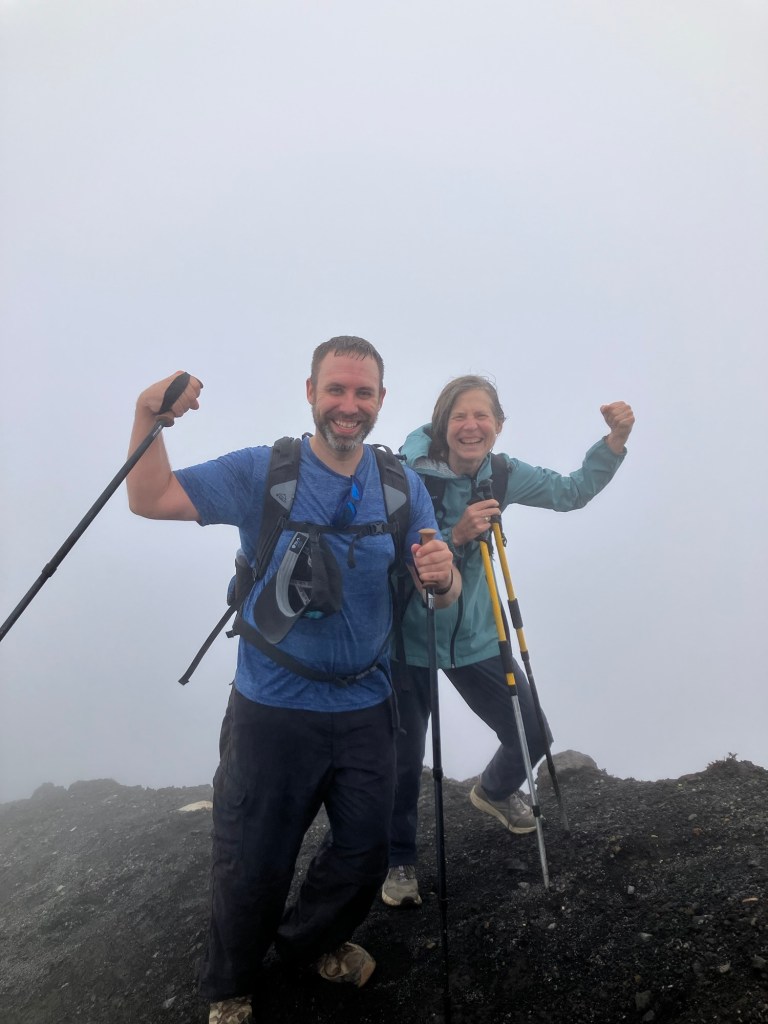

Four hours up, two through jungle terrain where the howler monkeys were busy forecasting rain. We reached the 1000 meter point of a 1610 meter high volcano and all was well. We stopped for water and snacks. One hiker chose to stay put at this location as we needed to pick up the pace to make to the summit by 12:30. Any later and we would not be able to make it back before sundown. So leaving one in our party behind, we proceeded to climb the intensifying grade that hadn’t yet been able to grow any foliage. We were hiking and grabbing onto the basalt rocks that came from the latest eruption in 1957.

After what amounted to only 300 meters but an hour later, we entered the clouds and were enveloped in mystery. Seeing nothing of a view or a distance to measure, we put one foot in front of the other and carried on. After 1300 meters, the hike was more rock climbing, the grade more vertical, more crawling up on feet and hands. We took breaks after every 100 meters, and not soon enough we made it to the edge of the cauldron. We could see nothing in all directions, but the euphoria of reaching such a summit was palpable. The gusts took our joy quickly over the sharply carved, lava formed peaks and made us unsteady on taxed legs, so after a few shouts of glee and pictures to later gloat over, we slowly made our way 4 hour turned 5 hour way back down. Once we arrived at the 1000 meter point where the jungle begins, the downpour began, turning the trail into a mudslide. Several slip and falls later, we arrive at the pick up point ten hours later, exhausted but accomplished.

loved the story!! You captured it perfectly, thanks for sharing – Louise

LikeLike

Thank you! All the best to you and to many more travels…

LikeLike