Oh DUBLIN!

We waited at the luggage carousel longer than necessary, watching the last few unclaimed bags go round several times and heard the awful gear shift stop the conveyor belt. We hated to admit it: our luggage did not arrive. It missed the connecting flight we made. By the time we registered the missing baggage and provided a forwarding address, using the arduous kiosk system, it was past 11 when we left the airport. We found the Dublin Express to bring us into the city, where at Merchant’s Quay it opened its doors to a chilly winter morning in Dublin. The missing bags and the few hours of catnapping over the Atlantic made us feel a weightless and untethered; just in time for opening hours at the Brazen Head Pub. The liquid spirits warmed our own still discombobulated ones after the short overnight transatlantic flight. Dublin was the starting and end point for a self-guided, two-week tour along the coasts of Ireland that Tom and I wanted to discover, and this pub, one of the “oldest in Dublin” – a multi-room, low ceiling, unlevel floor, low lights, dark wooden beams and polished bar, was an ideal representation of Ireland’s heart and pulse: camaraderie, hospitality, history and music. We were discussing our upcoming itinerary when we got to talking to an American couple sitting next to us and spent the rest of the hour sharing ideas, destinations, and driving tips before we realized it was noon. It was arranged over text that at noon, the host of the apartment we rented would open the gate.

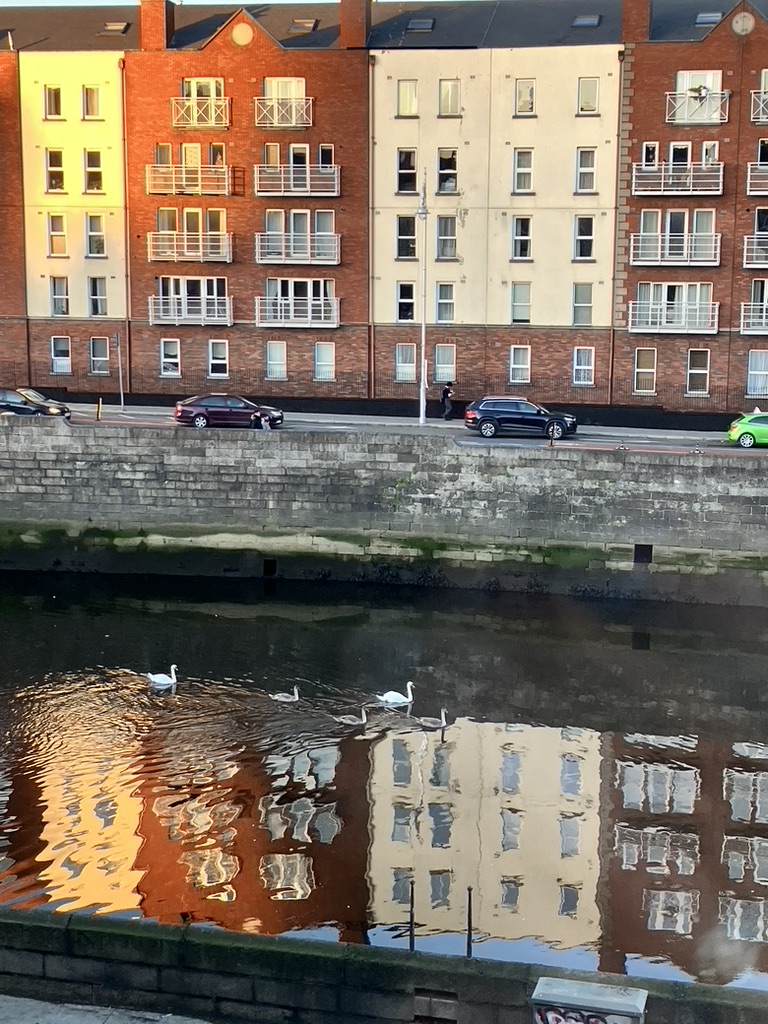

We located the apartment rental and contacted the landlord for entry information as he requested. There was a problem with the facade, how it didn’t look like the pictures he sent, and a gate that was not where it should have been, and the app through which short words and incomplete phrases of communication made understanding of a situation delayed and difficult. As it turned out, the host regretted his error and directed us to the wrong rental; ours was further west. A 15 minute walk later lead us to the correct premises and gate as indicated. We entered, found the appropriate apartment complex, the correct key pad entry, and walked in to a lovely cold apartment, whose large living room widows faced north and over the river. With heat and coffee, we settled in and spent a good few hours accessing the lost baggage site to update a new temporary address. I watched the ducks swim by on the river and the green double decker buses roll by on the quay, the chatter of engine and pedestrians on this winter weekday morning as I waited for the computer pages to load, the little circle going round and round in the palm of my hand. Once updated, we head out to Temple Bar, the historic section of Dublin now known for music, bars, and shopping.

The city exudes a young energy. People and traffic navigate and sweep through the city’s streets and over the river, the wind lifts the laughter and the honks and the sirens, the sounds spread out through the parks, the music and conversations and the chatter spill from open pub doors. Students file in and out out from the quad at Trinity, a graduating class in black robes flowing; and the churches, framing the history, stand sentinel with storied limestone pulled from the hills centuries ago. All of this creates a congenial personality in Dublin that is vibrant and inviting. Christmas lights and bulbs, banners and greetings hung from building top to building top, St. Patrick’s cathedral, its persistent hush, the peace and prayers accumulated over the years, the centuries, the wars, the faiths, the beliefs, standing and witnessing it all; the church: an innocent child of reformation separation, the prayers upon prayers, the souls of ancient places. Later that evening we had a pint at Fitzsimmon’s Pub lit up in white lights when the late fall sky turned dark. A duo on guitar and flute crooned into the microphones the old Irish laments, voices lifting the melancholy and the downtrodden, echoes of the past troubles and the promises ahead, singing the night’s sighs on the closing year.

The next day, through St. Stephens park, along decorated Grafton street where we found Marks and Spencers for a takeaway salads and sandwiches and the snack bag, finding a bench in the Trinity College quad and watching the students, any age, the professors, bustling to class, coming from a lecture, chatting and sitting, laughing and hurrying their way through youth the city, and leave the thinking of it all to the older ones on the benches. The Irish all around; the proud spirit, the claim of putting a place on the map. That second night, a pint at the Temple Bar where a duo with guitars belted out 80s and 90s classics – all universally familiar – interspersed with Irish “drinking songs” that nearly everyone in the packed bar joined in to sing. At some point that day the luggage arrived already looking smaller and less important than when we checked it, a day ago, but so long ago. Adjusted now to bearings, time and weather (so we think), we check out the next morning and drag the bags along behind us.

Working out the Kinks in CORK

How effortless it is to take a rental company’s new Nissan hybrid and take off. This car dings when it’s too close to a wall, a shrub, a pedestrian or a vehicle. When in reverse gear, the dash screen lights up in night sensor green to pick up what the naked eye can’t when you find yourself in the pitch black, moonless night having gone down a wrong turn on a dirt road. It has automatic windshield wipers, which know how quickly drops are falling on the windshield to coordinate their wiping, and know exactly when an oncoming truck thrusts a bucket full of water over the entire windshield obscuring for only half a second your already limited view by the grey afternoon twilight but long enough to temporarily suspend you in faith alone. It has automatic headlights and brights, which became extremely useful on the narrow country roads except when it believed a small cottage light in the distance was an oncoming headlight and then would suddenly shut off, leaving a wide enough swath of road eclipsed. You should be fine.

Understanding all of this digital and electronic help came later, when we needed it. We left the city fully loaded with gas, snacks, and verve for life. Just 90 minutes south of Dublin lives Kilkenny, a once medieval village on a hill that is now revived as a small city on the same, around a river and surrounding valley; its narrow streets are lined with the typical needs for living: shops, pubs, barbers, small groceries, computer and phone repairs, cafes, tea houses. Churches, an old castle that opens at 10 for a 10 Euro tour. We sat for lunch at the Castle and Tower cafe with pots of tea and sandwiches, giving us a taste of small village charm and an appetite for discovery. People shopped and sat around ceramic cups of tea and coffee, and the wait staff never disturbed with a check until it was asked for. We regretted leaving Kilkenny so early, but we felt we needed to grab the last few hours of daylight with which to see, and on went the vests, the coats, hats, and gloves to grab what we could of the remaining hours.

I had booked seven rental apartments along Ireland’s coasts and counties for our two week survey and finding our next apartment before dark became the mantra. Having chosen the first part of December to visit Ireland came with perks: access to attractions without reservations or throngs of summer season tourists, lower apartment and rental car prices, and indirect and sometimes direct contact with locals. Once we left Dublin, and to a greater extent Cork, the roads were relatively barren of traffic save for the delivery vans and farm trucks. This made driving the narrow, one lane roads into the heartlands of the counties quite pleasurable. However, December brought challenges as well. The ferry to the Aran Islands did not run, certain castles and museums were closed until March, and several cliff walks were closed due to the high winds. These were minor distractors, though, as every bend around Ireland offers something revealing to the senses and intellect. It was the diminished daylight of 54 degrees north latitude, flattened even further by the notorious cloud cover, the intermittent rain, the steady rain, and the misty rain that hindered opportunities to discover surprises on a spontaneous itinerary and flexible schedule. The times of the astronomical sunrise didn’t sound so bad but actual light and visibility with the aforementioned variables shortened this significantly – from around 7 hours of daylight to 6. All of which must be used to explore, walk, and drive to the next place before getting caught by the dark in the country without street lamps, lit signs, or as it turned out, a reliable navigational app. Of course, experience comes only after initiation.

Most of the written directions from the hosts to the apartments rented offered specific coordinates using an “eircode” that is similar to the US’s zip code. The eircode pinpoints the direct coordinate of a place on a map. Many of the cottages and apartments were on streets or tracts of land that had no typical postal number or street address, so the eircode becomes critically important. The Apple app I can normally count on for street numbers and names could not get me to an unnumbered, unnamed street as needed, and downloading the Google map app (that all the hosts in Ireland recommended) needed a Wifi connection. Realizing this in the dark, on the shoulder of a road, was in hindsight the one thing I should have planned for in advance. However, despite a delayed response from the host, and after spending an hour in the dark circumnavigating the area by driving 12 miles around and through the same roundabout multiple times, missing several exits, running a few red lights, chasing down a fictitious destination using faulty gps, we arrived in the general vicinity. We drove past a townhouse that had no porch light on that might normally highlight the number of the townhouse, no street sign nailed to its facade, no sign from anyone that indicated we were in the vicinity of where we ought to be. Instead we found a man hunched beneath a parka pacing out in front of one of the townhouses. We pulled over, rolled down the window, exchanged names, realized we were both searching for each other all this time, and were quite relieved. He pointed to the place in hasty deliverance, and then told us to park anywhere in the free public parking square fronting the townhomes.

He unlocks the door to a small ground floor apartment that opens to one main room for both the kitchen and front room; through a small hallway, a small bathroom with electric shower on the right side, a carpeted bedroom at the back. Manifur, as I’ve come to know him through our numerous texts to determine a coordination point, quickly turns on the electric heaters to maximum, and gives us the key. “Any questions, please text.” I thanked him by name. “Oh. I’m not Manifur. I’m Hamid.” Hamid must be doing Manifur a solid, but I am too relieved to give it much thought. We are inside from the sleeting rain, we have a warm bed, a door that locks, an undamaged car, and two feet each. A world awaits.

I wake to find in the kitchen a basket of single serving packets of dehydrated, ersatz “coffee, milk, and sugar” drinks I wouldn’t even leave out for Santa. I pull out the baggie of instant espresso stuck in a suitcase compartment and heat up a cup of coffee; I pour the dehydrated santa mix into another cup with muesli from our food bag. Now I was better able to assess the rest of the amenities. The utensil drawer lay empty except for one stainless steel soup spoon. The cupboards fared no better, providing only one dinner plate. There were no bowls, sandwich plates, or glasses. Although there were 6 coffee mugs and a french press, no coffee; a tea kettle, but no tea. There were a few pots, but no cooking tools. It looked like the Grinch had ransacked the kitchen. A strainer hung discriminately from a hook, perhaps for decoration, probably salvaged from Hamid’s extras in his own kitchen, waiting indefinitely for a use to strain something, anything. Maybe we are meant to eat with fingers. Maybe their last tenants had just cleaned them out. Maybe they thought everyone would take out at China One! around the corner. I pull out the baggie of emergency plastic fork and spoon from the other compartment of a suitcase and we split the plate.

Ready now for Cork, we head out wrapped up against the rain which proves forceful enough to drench us on the mile into town, so we make finding umbrellas a top priority once over the River Lee and into the historical streets of Cork. We notice right away the industry and factories and a working class feel. The Temple Bar and Grafton Street of Dublin is represented here with less acclaim on St. Patrick’s Street and South Mall: the department stores, the fast food chains, the name brands, the pubs, the bakeries, all with less area and width than in Dublin. Into one of these shops we found 7 Euro umbrellas, which held up for a km or so against the rain’s pelting and assaulting, but then gave up and flapped its spokes upward in surrender. I was continuously adjusting the umbrella back to its concave form by pressing and flattening it against what brick wall was handy. Nevertheless, layered as were in under armor, undershirts, sweaters, windproof vests, wool, double hats, gloves, and waterproof boots, it was a fantastic day in the rain, and in humor and in the kind of wet you enjoy because it accompanies a new experience, in a new land, it’s a delightful wet, and so we explored Cork.

We came upon the “English Market”, a large indoor food and artisan shopping area taking up a downtown block. Butchers, fish and cheese mongers, produce sellers, ready made fish and meat pies, freshly made baked goods, florists, and the occasional artisan of crafts gives a distinctive nod to Cork’s culinary delights and merits. Full tongues of cows and their hooves ready for a boil; local fish of all sizes shapes and colors unrecognizable. Unable to leave without stopping by the ready food counters, we picked up a fish pie (made from a whole assortment of white and pink fish), a salmon and leek quiche for dinner later at the apartment, and a few wooden forks and spoons with which to eat it. I stopped and sat for a rich dark, three shot espresso Americano at the cafe, the smells of cured meats and pungent cheeses surrounding me.

From the market we walked to St. Finbar’s cathedral, a giant landmark spearing the low hanging cloud covered skies of Cork with its belled spires, and from there along South Mall, back to the busyness of the historic district, ready for the next warm up. We happened upon Woodford Pub along a sidestreet, where we were warmly received. We were showed two seats along the wooden bar propped with draft handles of hops and ales and stouts and behind which was a mirrored wall with glass shelves of spirits. The proprietor took it upon himself to make my Irish coffee himself and told us a little bit more about Cork. It’s workers come from all over Europe; “The bartender is from Paris. There is a server from Belarus, and one from America, so as you can see,” he said, “Cork has a lot of immigrants” who go to school or work at the large Apple factory “up there.” He points behind him “How’s the coffee?” He asked me, as we both turn our gazes to the bottle of Killarny Whisky and then to my dark brown, frothy, spirited coffee. It’s one of the best I’ve had yet. “Delicious. Just right.” The conversation moved on to its other industries: manufacturing, IT, health, beer, and pharmaceuticals (not necessarily in that order). The young may stay for university, but once they graduate they tend to do what young people do: head out. We stayed and chatted a while on the upcoming election and the same issues facing Ireland as elsewhere: cost of living, immigration, affordable housing. Housing insurance, the taxes, the repairs. He and his wife have bought a place and – knocks on the wooden bartop – may be able to retire soon. He recommended a stroll through the park, a 20 minute walk west, and the History of Cork Museum located there. With new whiskey warmth, we headed out and walked through working class neighborhoods, practical, efficient, small one and two story townhomes, attached to one another as if posed for battle in a defensive line, all the way down the blocks, little in way of gardens but strong in graffiti artwork scrolled along the low cement boundary walls that kept them apart from the sidewalks. The green of the park announced itself as promised, and finding a shelter from the wet and surrounded in the aromas of soil and the greens of the still fresh grass, lush bushes and full trees, split the fish and cream pie with chilled wet fingers.

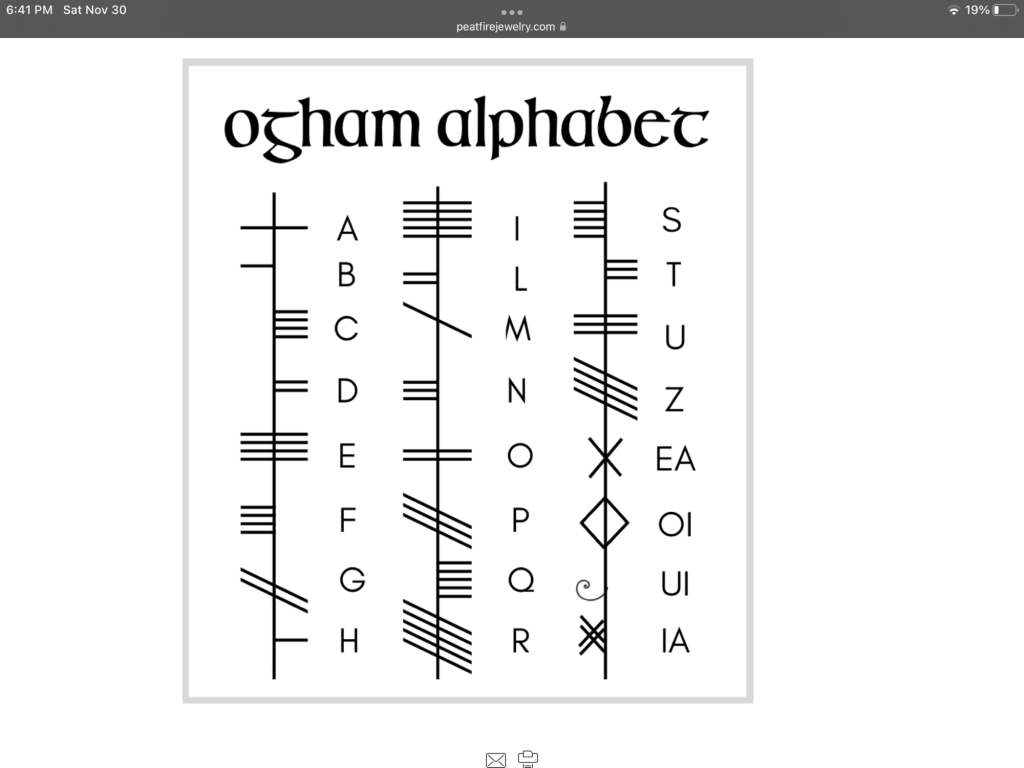

We had the museum to ourselves. Perusing the descriptions and artifacts, we learned that Cork was the hub in Ireland for silver, glass, and wool production, creating and exporting fine tableware and woven fabrics and cloth for homes throughout Europe until larger corporations and industries took over elsewhere. Shipping industries and manufacturing were dominantly portrayed in ledgers and photographs. and I was left with the impression that Cork gave itself a place and name through manufacturing, and still does today but with different products. Not to say the University College Cork hasn’t attracted a vibrant student body, as a later walk through its neo-gothic campus attested. Green landscape lights accented the turrets and arches, lit up the limestone facades; on the opposite side of the grassy quad, the student study areas were bustling with activity and the cafeteria, the library, and halls all buzzed with an energy of things being learned and studied; even the chapel had its door open, the nave lit up and a daily mass schedule posted; again, a more parochial feel than Trinity or University College Dublin but holding its own merits with the past and future echoes of significant writers and scientists. Along the breezeways, ancient stone slabs line the breezeways, chiseled with information in horizontal and vertical lines, from the ancient Irish language Ogam.

Under a setting sun and a purple-colored sky descending over southern Ireland, we walked back down into the hub of Cork, nestled between the rivers Lee, split into northern and southern tributaries at the east point of the city. On foot today, we enjoyed observing life after dark, that is, after 4 pm, and by this time became familiar with layouts and streets and landmarks; with the purr and groan of both hybrid and diesel engines, the chatter of people along the way, the Irish accents thicker, denser, elongated; the rougher and darker tattooed arms and legs in t-shirts and shorts despite the wind and rain. We stopped for a pint at a local nondescript local bar, sat at the window and watched as the bartender and patrons exited briefly every so often to stand outside and draw cigarette smoke from butts more out of necessity than enjoyment; watched the shoppers, bags hung on folded arms, one clutching their coat lapels against the rain, the other holding onto a sturdy umbrella; the young walking in groups, laughing and chatting and smoking into it, never a bother.

We wake the next day to the same rain, this time more severe in its pouring and wind whipping, and despite the flimsy umbrellas we bought whose purpose now seemed nominal (“Did you bring your umbrella?” Someone may ask you before a trip to Ireland. “Yes! All packed!”) decide to wait it out till 11 before driving to Blarney Castle. Once there, the rain lets up for a respite from the recent cities and into a lengthy, much needed walk through nature: wild woods and landscaped gardens, along the rivers Blarney and Martin, past farms with contented horses and cows busy with the green grass and through and up the castle, its walls and winding staircase still intact and bringing up thousands of visitors a year to the open roofed top, where, if you trust two blokes paid the state minimum wage to hold onto your legs while you dangle upside down along an exterior wall 85 feet from the ground, you can kiss a stone rinsed in centuries of people’s spit.

We return in the rain, in the dark, on the now familiar roads, and find leftovers for dinner in our stash: chicken vegetable teriyaki and fried rice from China One!, salmon and leek quiche from the English Market; Lidl’s brown soda bread layered with fork-pulled chunks of red cheddar cheese from County Kerry, our next destination for a few days.

The Colors of County KERRY

Kerry opened the skies for us, and we rolled into the county of stone demarcated farmland, fields nibbled to the quick, so that everywhere was a canvas of green and white polkadots. The sun peeked through cloud breaks and over their linings, and as dim and timid as it was, as much as it wanted to stay near the horizon and venture not so high, the sun still cast a golden yellow over the hills and onto the green Kerrygold fields. The wind on this day kept every element moving along; and on our way to Dingle Peninsula we met up with soft intermittent rain, quick and resplendent sun bursts, brilliant and unabashed rainbows, full spectrums of color, reaching right across the meridian.

We met up with the Atlantic in short time, and drove along the south shore of the Dingle Peninsula. It was here that Chet Raymo walked and reflected on science and God and nature in his book Honey From Stone. It was to this place that his book drew me, years ago when I read it, but never forgotten. I wanted to come feel the rawness of which he spoke, understand the mysteries in silent reflection, walk the ageless lands and rocks and muse under stars to get a little bit closer to understanding life at all. Unfortunately, it wouldn’t be on this trip. The rain had decided to stay on its last recent taking of turns; I had to keep my eyes on the small road leading into Dingle where we would get acquainted with the town by stopping for tea and at least attempt to get an impression of my own.

Dingle: a small fishing town cropped on the southern coast at the middle of the peninsula, jutting out into the ocean lashing its fury along the Wild Atlantic Way. It has learned to love its weather, its time, and its place. The wind came in east right off the Atlantic, bringing with it mist, rain, sea sprayed cold air and low clouds. Visibility was at a minimum, and umbrellas were useless against the onslaught. Yet people did their shopping along the three main streets that inched upward along the gently sloping hill, along colorful store fronts and inviting placards; they met up with friends, equally bundled up in wool and down and dabbled on the street curbs. Friends and colleagues gathered around outdoor pub tables, oblivious to the cold and rain sneaking in sideways under awnings and conducted their socialization, holding onto their pints as usual. We found ourselves at the Dingle Pub along the narrow and rickety Main Street, which appears to be the place. Dingle and the county is in the Gaeltacht Chorca Dhuibhne, a Gaelic speaking region, where Gaelic is spoken, practiced, and learned. Into the pub poured what may have been groups of students at terms’ end; one group was hosted by what I assumed to be the teacher, and her pupils all gathered around the hub of herself. I imagined the term over, the class dismissed to the pub and the language practiced in earnest. Included though at the bar itself were of course the young couples fashionably dressed, the older men who’ve come for the daily news, and the football watchers exuding random and sudden calls of shame or glory. We sip our tea. The warmth of it and the joy in the patrons brings life to this otherwise formidable piece of land.

When we leave, we are warmed and seasoned against the rain and chill, no longer disappointed or surprised by any of it. It seems out here the weather has the upper hand and so we mind it but go about the day. We find lunch at the Hare’s Corner: scrambled eggs and black pudding on thick slabs of sourdough and a stuffed breakfast burrito as thick and wide and full as a clutched baseball mitt. Afterwards, we slope back down to the harbor along Green Street and stop in at St Mary’s Church, walled with limestone and vaulted from the inside with wooden beams and roof. The wind whistles and whispers hauntingly, high up around the vaulted ceilings over the alter. Entering here, in this outpost to the sea, among the rocks and ancient stones and paths and prayers that have been here for centuries, millenia, it’s the breath of the place that I hear, and my own breath, familiar, alive, home.

We drive back off the peninsula and to our next apartment. We are greeted by a three legged border collie along with the other hosts Michelle and family. They show us the detached en suite room on this newly developed plot of land near Firies, which is between the cities Tralee and Killarney. On the tea service stand are lemon drizzle cake and raspberry cupcakes made by her girls, and should we want more to please just ask. The hours in the car prompt Tom to put on a yellow poncho, head out to do some walking along the dark and lonesome highway east of… well in this case, east of Farranfore. The wind must be whipping up and flapping that plastic yellow poncho around because it gets the dog barking for quite a while. I settle in with tea and cake and canvas maps for our Ring of Kerry tour tomorrow.

Many guides and guide books and itineraries exist for the Ring of Kerry, one of the top ten attractions to see in Ireland. The road outlines the Inveragh Peninsula, the next one down from Dingle, and can be driven clock or counterclockwise. Perhaps the most stunning route is to take it clockwise from Killarney, and catch the morning light rising onto and between the high hills of Killarney National Park, worth a complete day of exploring all on its own. Replete with lakes, meadows, hills, trails and an old castle or two, it speaks to the glory of nature. Very little needs to be added here that will compliment its beauty. Suffice it to say that on this day, the sky and land worked together to create the most specatcular views and impressions of nature I had yet to see in a long time.

The peninsulas that reach into the Atlantic along the southwest coast of Ireland, and the body of land to which each is attached – from the River Shannon in the north, across Limerick, and down around the east of Cork – this whole area on the map – looks like a giant bear left its paw print when it walked over the world in the days of lava and molten moving rock. Each of the claws claws jut out from its pad, forming the pensinsuals, and the cliffs of Kerry, just south of Dingle reach into the dark blue depths of the ocean, tired yet wild, an ocean that has finally reached a shore. Waves spill and splash their way into cauldrons far below from up here on wind formed, crested hills high above. The breadth of the sky from this world’s end, and the breath of life cascading unhindered from far and wide spews and sifts a vitality over us, it awakens us and steels us to this moment, at this ocean, this world, this infinite wonder. Striations of color in the sky, the harmonies of a canvas strewn with grays and blues of sky reach like fingers into my soul and burn in equal wonder as the splendor of blues and black and white crashing against the knife sharp edges of rocks. Streaks of purple sear across the horizon; green and yellow tundra both soften and spear the cliffs of rust colored foliage swirling all around.

Strong coffee in Portmagee to wake from this meditation; the fishing boats tethered like hunting dogs to their kennels, waiting and pitching, waiting and waiting the dark nights out. We continue along he narrow road winding around and over fertile sheep cropped tufts and hills plotted with slate and limestone rock slices stacked on each other so long ago, still standing. My heart is heavy, full, fed from unmarked ways that bring us to our destinations: the washing from the rain, the sharply wind eroded edges we face, wild waters we are carried away by and currents on which we return.

The Cliffs at CLARE and Getting to GALWAY

I downloaded the Google Map app that Ireland seemed to agree with best before we left Michelle’s to spend the day driving north to the Cliffs of Moher and the next B&B in Barna, a small suburb, just west of Galway city. The Shannon ferry brought us across the River Shannon, a long inlet from the Atlantic Ocean carving its way to Limerick. I wanted to do more of the WIld Atlantic Way, and stuck closer to the coastal roads than head back inland. The three legged dog Filligree watched as we hoisted the bags into the car; I bagged the rest of the cupcakes and off we went.

A short half hour later and we were at the Shannon Ferry terminal and waiting for the small boat to take us the twenty minute crossing. We were only 9 cars that day and no walk ons; the overhead clouds were high and so there was little rain, but once on the ferry we sailed through a little cyclone and the rain fell for about three minutes and then moved on, and once again a rainbow appeared over the river. I’ve never seen such full and wide rainbows before this trip; sometimes they seemed so close to us, their wide colored bands falling just behind a nearby crop or in this case right into the water, only meters from us.

The Cliffs of Moher landmark attraction is undergoing restoration and “widenation” projects, as I call it, to accomodate the large amounts of seasonal visitors. Although on this trip relatvely few tourists have impacted our wait times or drive times; the roads have been empty and the pub tables can be snagged, there are many indications that Ireland is still a fully embodied Christmas and winter destination, as Churches are open, mass times regular, and the guitars and flutes continue to sing out from pubs where you can still snag a table for a listen. We hadn’t come across any fiddlers though, save one on a cliff at Moher. Music started early in Dublin, but it never got started in Cork, Dingle, or Killarney until 9 at the earliest. So out here was the fiddler, cold wind biting into her finger tips on the fret for the sharps and minors of Irish ballads, over the cliffs and recalling the heart of every Irish movie we’d come to love. The restoration project is an ongoing affair that had the cliff side trails closed from points both south and north from the center area. Farmland comes right up to the cliffs, and these are more sheer, cut by weathering neatly, and the water comes up to a sandy and flat shore gracefully, with ease and patience. We walked along the cliff for about a half hour; in warmer months, musicians would stake out a “pitch” – a place where they could play their instrument without it interfering with the next musician. On a previous visit, I encountered a harpist whose plucking mesmerized visitors. Music is part of the fabric here, and the wind carries it and winds it around your soul.

We arrive in Barna in the dark, sometime after 4, and the newly acquired GPS leads us down unlit one-track farm roads. I memorized as many of the directions before arrival, but some of them were indeed a maze. An excerpt from the welcome text reads: We live in a rural community with no house numbers & no street lights at night so it may also be helpful to use the additional directions that are provided at the end of this message. We are two doors up from M— & R— Veterinary Clinic. Watch out for P—- engraved on the stone wall. Pull into the front driveway and park at the FRONT of the property in the designated parking space for the Retreat. Follow the signs and these will direct you around the left side of the building and towards your entrance which is at the REAR. There are two guest suites on the property so ensure you are at the correct one… it is clearly signed on the wall…. Coming from Galway city on the coast road R336 (with the sea on your left) as you enter Barna Village turn right at the traffic lights at the hotel . After approximately 100 metres take the first left turn ( NOT into the housing estate or the following cul de sac) & then take an immediate right turn. Our house is the [nth] on the right, two doors up from the clinic. We arrive at the intended intersection (“It’s around here, somewhere,”) with only a few reverse and U turns, and slow drive bys, by carefully looking for landmarks indicated by the directions. We pulled up to the correct house by simply stopping for a bit to get oriented, and looking to our left, found we had stopped in front of the right place, according to the sign on the stone wall, hardly visible without any gate light to indicate its presence. We had come to the end of the labyrinth. We enter, find the right parking spot, and then the right door, the correct entry code, and arrived at another very modern ensuite room draped in what we considered luxury: a large bed with soft linen and heavy covers, silence, complimentary beer in the fridge, and coffee for the morning.

Check out was at 11 and we were in no hurry. Instead of rushing out to grab daylight and visit Galway, we lingered longer in the hot water shower and bath, at the breakfast table with pots of coffee and tea and complimentary bagels and cream cheese. The raw scrub brushing wind from the cliffs, the odorous humus from the wet farm fields, the rainbows splashed across skies – all of that we still carried with us and weren’t quite ready to counter it with the man made, albeit very creative, culture of Galway, especially after skirting around it last night and experiencing heavy traffic on the way in and out. So we ltook advantage of the morning by simply being, and left at 11 to drive further north and into County Donegal, which feeds the darkness even more and robs the day of even less light. I was driven into these fantastic skies whose darkness let my soul out, naked and clamoring for breath. I needed more.

The Delicious Dark of Donegal

The Green gate became the marker for our next cottage out in the twilight of Stragally, near Ballybofey, County Donegal. With sparse daylight to spare, we left the main road from Ballybofey, a ten minute drive according to Google maps to this green gate of our next destination, but actually half an hour to the uninitiated. With a more accurate GPS, I felt more confident, but that green gate needed to be picked up by daylight, otherwise they would all look black. Most country roads allowed drivers speeds of up to 100 kilometers per hour which appear to wind ever more narrowly around bends and hills, the more north and rural we drove, making visibility for oncoming traffic evermore difficult and unpredictable. We may be driving for several minutes along such a road coasting at a cautious 40 km taking in the scenery and lulled by the rolling and dipping and the quaint one lane stone bridges long enough to believe we own this, we got this, only to be met head on with someone who actually does have it, this road, at this time, who wasn’t expecting the wandering rental car taking the air. But with heightened senses and caffeine jump started mornings, I was able to quickly react, and each of us quickly veered just slightly to our sides and one of us, usually (us), giving far more leeway than the other. Ding ding ding! went the car’s sensor. The surprises came from the rear as well. Springing out of nowhere, well, probably out from the sleepy hills and grassy, hidden driveways a car would appear with such speed into my rear view mirror it was likely they’d forgotten something they’d left up ahead, like a child or a sheep, because they came close enough to take chunks out of the rear in polite suggestion I hasten it along. On these occasions I pulled over where I found enough access to let them pass and get their kids to or from that grade school we pass on our way into town or to round up some sheep that sprang a fence. I can’t imagine a hurry for anything else out here. I thought I could always hear them, sighing in exasperation, saying finally! as they swerved around and on, taking the curves at a comfortable 100.

It became a game – this navigation to the next cottage, apartment, home before dark – that when successfully found as per the planning and organizing with space and time in otherwise unfamiliar environments, we felt we had come out ahead, with some advantage. There was space and energy left over that we kept in reserve for stressors like nightfall, narrow, unmarked roads, headlights that considered the comfort of the oncoming driver’s eyes more than ensuring I stayed on the road, misleading gps, no signal zones, and Gealtacht regions which only used Gaelic. These were all or individually part of the incidental variables that met us along the roads, so when we arrived as scheduled with witts attached we could now use that reserve for things other than dealing with stress. There were arrivals, still early, but yet so dark, after which nothing could be thought about but for the glass of wine. Other arrivals equipped us with confidence to leave a perfectly found place and venture into the dark, knowing that we tamed it into submission, and explore the nearest town. Often we did crave light, life, and lyrics to break up the dark hours, and simply a walk around town was enough, hear the banter and the music coming from shops and pubs, or a shop through a new grocery and price compare (“Should we get more cheese? How are we doing on nuts?”) before the comfort of our own warmly lit guest residence waiting for us drew us back over the dark roads home.

It fell within the latter example when we found the green gate, and even more so when it opened, and we road down twenty more meters to the front of the small three bedroom remodeled farm house to find the key under the antique butter churn. Using the french doors on the side of the cottage, we opened to a modern kitchen, behind it the original main room with fireplace (now replaced with a wood burning stove) and behind that the added-on bedroom. We turned on the heat and lights; listened to the welcome hum and settled around the butcher’s block kitchen table. A blanket of green surround us on all sides, folding over and under hedges, farm fields, pastures, crops of trees, stone and fence walls. Behind us, up the hill, the few houses along the farm road. Sheep appear and recede in quiet movements, cushioning the silence their intermittent bleats.

Later that evening, after a return from the “ten minute” drive back into Ballybofey to the Lidl to replenish supplies for our three day stay, we walked along the rutted farm road that lead to the property. The clouds had broken apart, drifted away, and for an hour we walked and stopped, back and forth in this deliciously formless world staring straight up at the moonless black night, studded and pierced and splashed with stars blazing and burning from horizon to horizon. The universe floods the Earth with its love. It is no more mysterious than the complexity of love, no more infinite than our capacity for love. We look up and see a mystery, but it’s simply our own that we see reflected back to us.

The kitchen faces east, and that next morning, still under a clear black sky, the horizon bled red. For several minutes the color held fast, like tempura paint. Then ever so gradually, the red leaked into orange and pink, giving way to a purple sky, as if a painter held a spray bottle to it and moistened his canvas with ocean water. A sheep slowly walks into this tableau, nibbling at the new overnight sprouts, looks up, and our eyes meet. A thick, dirty white wool covers its husky frame, not a shiver or complaint rippling through its fat and muscle. It lowers its head, moves on, uninterested in my musings from this Theatron seat in soft light and electric kettles. I feel as if I’m part of an audience to an ancient play. Gradually, the skene, the backdrop, introduced a bank of thick clouds, arriving as if hitched to and pulled by the sun, leading them to rest over this island nation.

The next two days were devoted to getting acquainted with the small village of Donegal, at the mouth of Donegal Bay which narrows into the River Eske, and around which the town was built. One small triangular roundabout centralizes the three main streets that meet here, and in this triangle a Christmas tent and banner were announcing Christmas festivities; lights and wreaths hung in anticipation. Two butchers, a grocer, a few cafes with breakfast and lunch offerings, a few pubs for the evening meals and drinks. A castle, two cemeteries, one dedicated to the famine victims of 1849-1860, up the hill, the other overlooking the river, its Irish crosses and blocks of marble tilted but holding; its weathered tombstones in various stages of decay, chipped and whipped by the cold salt wash, lifting names and dates to the wind, letters and numbers sinking into the stone. We walked out of town up the hill, away from the water and onto a walking trail that fed into the heart of the county, greeting the light rain as it came with no more than a shrug and a kiss, tracking the low clouds and fog as it hung over the meadows, ruffling the thick coats of wool – ours and theirs, those wooly, oily tresses keeping the rain from dampening their day, and rainproof gear and flimsy umbrellas ours. We returned along the same tracks, stopped at the grocer, and ate warmed salmon and creamed potato casserole in the stone cottage under soft light.

Glenveagh National Park was our second day destination, a short drive to the north central part of the county. It has hiking trails along its major lake, Lough Veagh, and a few that extend perpendicular to it; one that leads to an estate castle that has seen its change of ownership since it was built. We were introduced to its history with information in the reception hall. Its first builder and owner, was ruthless Anglo Irish John Adair who created animosity between himself and the neighboring farmers by requiring them to pay a tax, and soon evicted a significant farming population when relationships became too tenuous; at one point one of the castle tax collectors was found murdered in the hills. But he died one day, coming back from the US on business, and his wife took over the property, bringing a sense of restoration to the gardens, grounds and relationships. Upon her death, it lay abandoned for some years before an Arthur Porter, archeologist from Harvard University moved in to study Irish culture. Unfortunately, he disappeared one day when he was off exploring the Inishowen peninsula, just up the road. The last owner was a Henry Macllhenny of Philadelphia, whose roots and ancestry originated not too far north, in Donegal, and he came home to roost and cultivate the gardens, until 1975, when he sold it to the Office of Public Works, which created it and the surrounding acres into a national park. “Feel free to wander,” the receptionist told us, “But there is a storm coming around 3.” From the recent wind and rain activity we’ve experienced in these past days, we weren’t quite sure what a storm might entail. “Heavy heavy wind, lots of rain, and flooding in areas.” We checked the time; we looked to the sky; we consulted the map of yet undiscovered nature trails, and felt we needed to make adjustments in light of the threat. As we returned to the car park along the scenic level trail along the lake, the wind picked up and the clouds out west were getting dark. It seemed to be a normal day in Ireland’s wee daylight. The surrounding mountains have soft tops and and its once bright colors have gently folded up for the winter in faded greens and browns, mellow and patient for the solstice.

The Good Storm of Antrim

Escaping the more forceful winds and flooding expected in County Donegal, we arrived safely at our cottage, and as the night descended and nothing in the form of gales and floods shook the rafters or hammered the windows, we chalked it up to having blown somewhere else in some other county or blown right over our heads. We woke to a red sky (sailor’s warning?) but a clear morning; we were in luck as we set off to the northeast and across the border for the drive along the highly suggested Coastal Causeway, one of the more breathtaking regions in Northern Ireland that, according to the guide books, must not be missed. We drove through the now familiar fields and villages, fields now shared by both sheep and cows, villages with street signs sharing both Gaelic and English; other villages in English only and flying the Union Jack. We stopped for tea time in Portstewart, at one of the first establishments we found that sat right at water’s edge and the tumultuous North Atlantics waves. It happened to belong to a golf course, which was right next door, and wool vested and capped golfers met their own tee times in full swing despite the gently beginning rain and breeze pick up. The rain came became steady as we veered north to the coast, but inured to it by this time, didn’t pay it much mind, and so didn’t realize how quickly it consumed us until we were somewhat navigationally debilitated by it. The rain and wind pelted the solid rental and sent its windshield wipers into a flapping frenzy; visibility was down to the next corner, whose attention under the circumstances took precedence over the trailheads. Apparently we drove right past the trailhead to Giant’s Causeway that leads under caves and over splendidly cylindrical stones formed by centuries of particular erosion; signs were few and suddenly appeared out of the rain too quickly before we were past them, and the gps had lost all reckoning. Storm Darragh had found us.

Waiting out the storm did not appear a likely option. We drove south from the coast, towards Ballymena and the accommodations waiting for us. We picked up a signal somewhere along the road and directed our sights through the rain and several roundabouts later, came through the property gates flooded not with water but with stage lights, the lights of a production company. Richard, the owner, came out to greet us in rain gear and umbrella, and told us the grounds were being used for a BBC drama series set and they were just wrapping up. We could see why the location was ideal: We entered a courtyard around which a main house, barns and stables were built all out of stone, and whose wooden doors were all painted in brilliant red. Inside, and a few steps down to a large kitchen with a heated floor, a tea kettle and a small electric radio on which I found several channels of BBC news and music. Upstairs, a living room, upholstered in rose flowers, cloth shades in like patterns, and old glass windows that rippled slightly to views of the wild garden below.

The storm prevented us from the last remaining itinerary planned for the trip: coastal walks and a tour through Belfast. Trees were down, cutting off roads, and the busses and trains were halted. But this respite from schedule gave us time for reflection after days of sense saturation. The storm passed, clearing the skies and roads for the drive back to Dublin, the trip’s conclusion. A storm brings change. Sometimes it comes along swiftly, without a request, like a rogue wave that capsizes stability. Sometimes it arrives slowly, methodically planning its approach steadily. In either case, it comes and like a winter’s darkness, we watch and wait and listen for the clearing that takes us home.